Doctors for Dignity Advocate Dr. Seth Morgan Reflects on End-of-Life Options and the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Jul 19, 2021 D4D Doctors for Dignity Doctors4Dignity Dr. Seth Morgan

This month, Doctors for Dignity recognizes the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), a landmark civil rights law passed in 1990 that prohibits discrimination against people living with disabilities in all areas of life including employment, education, transportation and communication.

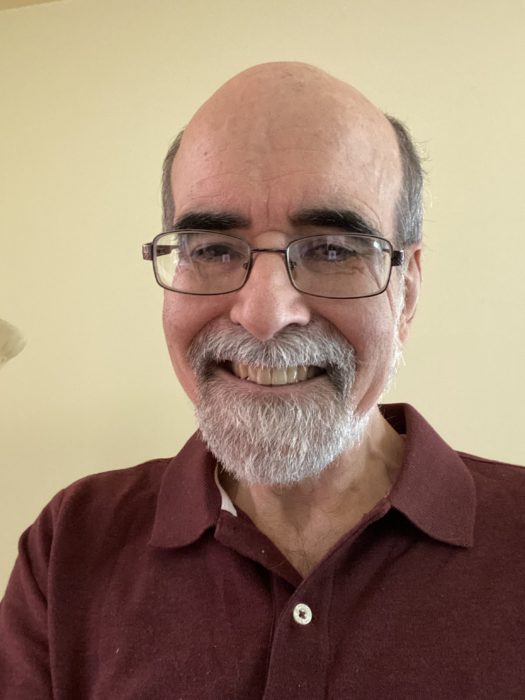

This year, we are chatting with Dr. Seth Morgan, a retired neurologist living with Multiple Sclerosis who is also a strong advocate for patient autonomy. Since leaving his medical practice, Dr. Morgan (who prefers to be called Seth) has become deeply involved in disability rights advocacy and is a strong supporter of medical aid in dying as an end-of-life option for terminally ill adults.

We chatted with Seth online and asked him to reflect on both the ADA and his personal and professional experience living and treating MS. Read more about Dr. Morgan here.

(The interview below has been edited for clarity. The opinions expressed by Dr. Morgan during our interview are his alone and do not necessarily represent the positions of the various community groups he volunteers with, or their members.)

As a neurologist you cared for many patients with MS, before being diagnosed yourself. Now you are a huge disability rights advocate. Can you tell us a bit about your path?

I went to George Washington University for medical school, where I also did my residency in Neurology. I went into private practice in the Washington DC area as a general neurologist. During that time I'd see people with MS, Parkinson's, strokes, epilepsy - fairly standard for a private practice. I was actually very frustrated with my ability to take care of people with MS, because we really had no tools with which to prevent attacks at that point.

About 21 years into private practice, I diagnosed myself with Multiple Sclerosis. I continued to work for a couple of years and then because of my vision and cognitive issues, I really struggled keeping up on the literature. I went to my group of neurologists and said I was going to retire after 23 years of taking care of patients.

I was very depressed for the first few years, having lost my job and my profession on top of the new diagnosis. Eventually, I looked at my situation and realized I could still do things, and use my expertise. That's when I called the MS Society. They said “Hey, you know about the disease, you've lived it and you've treated it. Why don't you come to Capitol Hill with us?”

One thing led to another. My passion for issues that affect people with disabilities expanded to the point that I became a member of our county commission on people with disabilities, and then expanded that to become the chair of the commission. I have also served as the vice chair of the Alliance of Disability Commissions and Committees for Maryland, and a member of the Maryland State Commission on Disabilities.

And since then I've been doing nothing but advocating and this is what I love to do at this point. It's my second career.

What has led to your advocacy for medical aid in dying?

I came to it originally because both of my parents unfortunately had very poor end of life experiences, experiences that I knew if they could just be out of their body and watch what was happening, they would never have wanted to go through what they went through.

As a neurologist I had many patients who did want as many options as possible, and I was always ready to give them that. There were also people who told me they knew they wanted to die on their own terms, and were ready to stop treatments. At that point there were no medical aid-in-dying laws on the books, but the medical profession had been addressing the issue for years. When someone is terminal and asking for assistance to be kept comfortable, there were times when we would give what was called a “terminal sedation” in the intensive care unit. Most doctors did it, many still do, and it just pointed out to me that we needed a better system for people being in control of their end-of-life experience.

So I set up family meetings for those individuals, to avoid any occasion where loved ones would not follow through with their wishes. When that happens, it is often because the family is not on board, and are scared. I would invite my patients to share with their family and then I would be there to answer technical questions. By doing that, I was able to better support patients who wanted to be kept comfortable at the end of life, and wanted to be more in control.

Between my family experience and my professional experience I came to very strongly support medical aid in dying, and other end of life options, understanding that an option is not going to be right for everyone, and should not be made by anyone but the patient. If the patient wants everything done to the very end, so be it. But if they want comfort and control of their end of life experience, then they should be allowed in the situation of being in a terminal illness to be able to control the situation in which they end their life.

You have testified in favor of the Maryland End of Life Option Act in the past, and have spoken to those opposed to it. What have you shared with them?

Ultimately, I understand that opponents feel very strongly about it, and I respect that. But my feeling is that everyone should have the ability to make a decision, that it shouldn't be something that is mandated across the board by law or religious belief. One of my frustrations is that many of these folks in opposition say that they are speaking on behalf of people with disabilities. But to me, there's no group that can speak for everyone with a disability, and that goes for Compassion & Choices, and any other groups.

Everyone should have the ability to make their own decisions. Some don’t want to have access to medical aid in dying for instance, but should the need arise and their end of life experience be so uncomfortable, they should have that ability to choose.

We utilize the word Dignity in our work. What does that word mean to you?

I believe that you get to decide what is dignified for you. Dignity is having choice in your life. Dignity to me is autonomy. It's the ability to say I am a person, I have my own beliefs and feelings, and I should not be forced to make choices that don’t feel right for me. Nobody speaks for me. Ableism shouldn't make people with disabilities unable to use an option at the end of life.

This month, we are highlighting the importance of the ADA and the advocates who fought for its passage. How would you describe the value and importance of the ADA? Please share some of your first-hand experiences.

The ADA is such critical legislation. I think that people reference the ADA for its requirements, or determine what is or is not covered by the law - but it’s just a starting point. It's a place where we begin, but it is not the endpoint.

What the ADA has done is create guidelines to notice inequity. It allows us to call for accommodations in education, and a chance for a job we are qualified to hold. In Montgomery County where I am chair of our commission, we were one of the first counties to actually prioritize qualified applicants who have a disability. I am so very proud of that work. The ADA provides support through reasonable accommodations, career expansion options, and a platform to push for change. Essentially, it was created to support our ability to have a personal choice, that's what we're talking about in the end-of-life movement.